By Gerhard Stahl

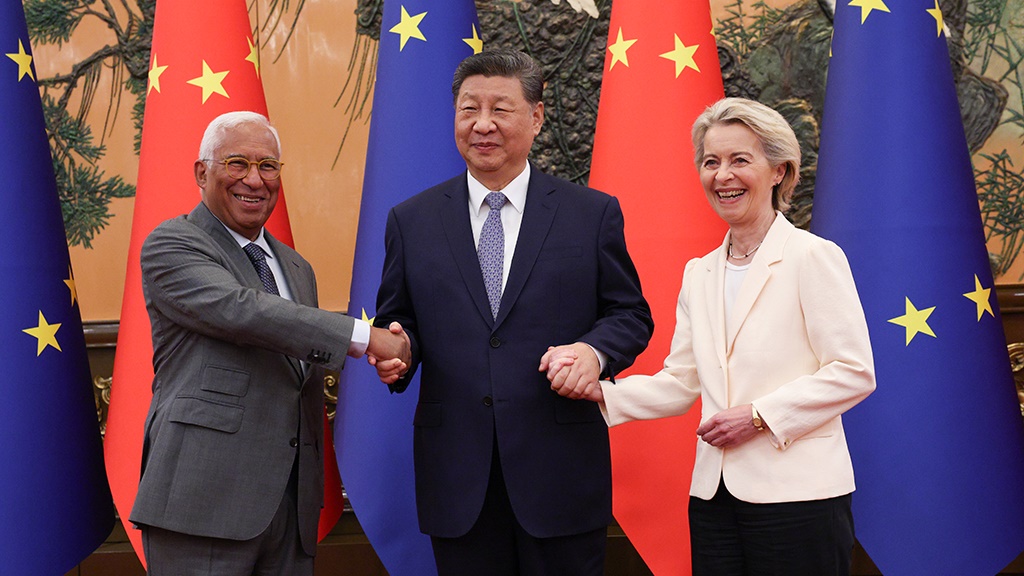

In 2025, the European Union and the People’s Republic of China mark the 50th anniversary of their diplomatic relations. This milestone will be marked by a summit on 24th July in Beijing. It comes at a moment of profound global transformation: geopolitical conflicts are escalating into wars, global institutions are losing effectiveness, economic interdependence is under pressure and international norms are being challenged.

EU-China relations, once largely shaped by pragmatic cooperation, are increasingly defined by rivalry and mistrust. The EU’s 2019 ‘Strategic Outlook’ captured this shift, describing China as a partner, competitor, and systemic rival – a formulation now echoed in national governments and public debate.

Yet the term ‘systemic rival’ has contributed more to misunderstanding than to constructive dialogue.

The prevailing framing of global politics as a contest between democracies and autocracies has further strained relations. Tensions peaked when the European Parliament suspended ratification of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), a deal that had taken seven years to negotiate and was finalised in the final days of Germany’s Council presidency in December 2020. The CAI promised meaningful concessions on market access and investment conditions for European companies.

However, ratification stalled in response to EU sanctions on human rights grounds, China’s countersanctions and US opposition. Ironically, the Trump administration had signed a bilateral trade deal with China in early 2020 – without consulting the EU – to secure purchases of American goods.

Today, European democracy and integration are threatened not only externally, but also internally, by populist movements on both sides of the Atlantic. The MAGA movement, which propelled Donald Trump’s political return, is now actively supporting far-right, Eurosceptic forces in Europe. Against this

backdrop, the EU-China summit must help reset relations under new international conditions. The meeting offers an opportunity to realign expectations, restore trust and recommit to engagement based on clearly defined interests and responsibilities. It is not just about bilateral cooperation – it is about the future of the global order.

Trump’s return: a structural threat to a multilateral order

Donald Trump’s return to the White House is not merely a domestic shift – it marks a rupture in the post-war international order. His administration embraces a protectionist, transactional, unilateral worldview – undermining an international system that has underpinned European peace and prosperity for over seven decades. Trump’s resurgence reflects deeper structural challenges. The United States has failed to distribute the gains of globalisation fairly. Deindustrialisation, stagnant middle-class wages and rising inequality have led large parts of the American electorate toward populism, nationalism and protectionism. Global Markets are no longer seen as sources of wealth but

as threats to identity and security.

The consequences are far-reaching:

• Withdrawal from global institutions: The US has previously pulled out of the World Health Organisation, the Paris climate agreement and continues to block the WTO’s dispute settlement system;

• Weaponisation of economic policy: Tariffs, sanctions, and export controls are used as tools of pressure, without regard for long-term partnerships or shared norms;

• Confrontation with China, which is now widely seen in Washington as the central long-term challenge to US dominance.

At the core of this confrontation lies a fear of a multipolar world shaped by China’s rise. A successful China – capable of establishing alternative financial, trade and development institutions – could undermine the US dollar’s role as the global reserve currency. This, in turn, would weaken America’s economic and financial power and global influence.

Europe’s dilemma: between US unilateralism and Chinese ambivalence

Europe has no fundamental problem with a multipolar world. The age of European global empires is over. EU member states, relatively small on a global scale, have learned with European integration and the establishment of the single market to adapt their national economic and political structures to changes. But current developments present specific challenges.

The US, Europe’s closest ally and security guarantor, is now pursuing a foreign and trade policy that is increasingly self-interested and, at times, harmful. Meanwhile, China – one of Europe’s most important trading partners – offers more long-term predictability, but also acts as a strategic competitor with an ambivalent approach. China’s model of a socialist market economy – with stateowned enterprises, special economic zones and subsidies from national and provincial governments – raises serious competition concerns. Its industrial policies with high investment rates, low

consumption levels and slow pace of market liberalisation distort global competition and threaten jobs in Europe. Yet, at the same time, a growing middle class of over 400 million people and a potential consumer market of 1.4 billion continue to present great opportunities for European businesses.

Europe must chart its own path. Aligning with Washington’s confrontational stance would undermine European economic and political autonomy and accelerate global fragmentation – especially damaging for an export-oriented economy. At the same time, engaging China without clear conditions would be short-sighted and risk one-sided dependency. The EU stands for an order based on law, cooperation and shared institutions – an essential lesson from Europe’s wars and painful history. This

model can serve as a global alternative to destabilising national power politics. To develop a rulesbased order, however, partners are needed. If the US cannot – or does not want to – uphold the multilateral system, the EU must seek new alliances. That includes offering China, despite all contradictions, a path to constructive engagement.

Trust deficits: economic and political tensions on both sides

For any renewed engagement between the EU and China to be credible, both sides must confront the deep-rooted structural grievances that continue to erode trust. On the European side, key concerns include persistent market access restrictions in China, industrial overcapacities driven by state subsidies and a lack of reciprocity in areas such as investment and public procurement. European firms also face challenges related to forced technology transfers, insufficient protection of intellectual

property and an opaque regulatory environment that restrains e.g. access to rare raw materials. Compounding these issues is a growing trade deficit, which many in Europe attribute to China’s continued reliance on an export-driven economic model.

Another source of concern is China’s increasingly close relationship with Russia. Beijing’s economic support for Moscow – particularly through energy purchases and dual-use exports – is widely perceived in Europe as indirect assistance for Russia’s war in Ukraine. From China’s perspective, however, the EU also bears responsibility for the current trust deficit. Chinese officials point to what they see as discriminatory treatment of Chinese companies, including restrictive investment screening, tariffs and procurement rules. They view export controls and sanctions – often justified on the grounds of national security or human rights – as part of a broader effort to contain China. This is seen as an indication that the EU joins the US’s confrontational policy. There is also growing frustration with EU member states aligning more closely with expansive US military strategy, such as NATO’s interest in the Indo-Pacific. On Taiwan, Beijing worries that the EU’s ambiguous stance could undermine the long-standing ‘One China’ policy. Altogether, China sees the EU as lacking strategic autonomy and acting more as a junior partner to Washington than as an independent global actor.

Priorities for the summit: rebuilding trust, enabling cooperation

The EU-China summit represents an opportunity to reset the tone of the relationship and lay the groundwork for a more stable and constructive phase of engagement. Both sides need to reframe their relationship. The EU must go beyond the simplistic label of ‘systemic rival’ and offer China the opportunity to become a partner for a stable, rule -based international order. China faces a strategic choice: whether to pursue a ‘China first’ course or to act in line with its stated vision of a multipolar world offering win-win cooperation.

First, the summit should be able to solve some of the urgent trade problems like access to rare earth resources, a common understanding of WTO compatible use of customs duties, and a consensus that neither the EU nor China will agree to trade deals with the US at the expense of third parties.

Furthermore, the summit should go beyond day-to-day questions and emphasise a shared

commitment to sustainable development and a rules-based global economy within a multipolar world guided by international law and effective multilateral institutions.

A key priority should be the relaunch of constructive economic dialogue. Talks on market access, reciprocity, and industrial subsidies must resume in earnest. The EU should make clear that it will take safeguard measures to protect its economic interests if meaningful progress is not achieved. At the same time, both sides could explore an updated framework for investment cooperation, potentially reviving core elements of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) under revised terms. Strategic tensions must also be addressed through regular dialogue. This includes discussions on major

geopolitical flashpoints – such as the war in Ukraine, and the growing militarisation of the Indo-Pacific – to avoid miscalculations and clarify red lines.

In parallel, the EU and China should launch joint initiatives in key areas of mutual interest, particularly climate action, green finance, artificial intelligence governance and digital standards. These domains can serve as flagship areas of cooperation and shared global responsibility. To succeed, the EU must signal its strategic autonomy by engaging China based on its own interests and principles, rather than as a proxy for broader US containment strategies. Lastly, both parties should commit to the reform of international institutions (WTO, IMF, World Bank and the United Nations) to strengthen multilateralism, allow countries of the global south to be better represented and resist the drift toward unilateralism and national power politics.

This year’s summit should be a moment for open dialogue among political leaders, with the goal of charting a new course for EU-China cooperation in a world looking for a new international order.

Article first published on: https://makronom.de/was-beim-eu-china-gipfel-auf-dem-spiel-steht-49407

Author: Gerhard Stahl, Peking University HSBC Business School, member of FEPS’ Scientific Council, former Secretary General of the EU-Committee of the Regions.